Ian Burn et al. is a long research query focusing on the legacy of Ian Burn, and the work of his network of peers. A series of public events, publications and writing follows:

Ian Burn et al. is a long research query focusing on the legacy of Ian Burn, and the work of his network of peers. A series of public events, publications and writing follows:

This evening presented two slideshow essays:

A reconstruction1 of Walt Disney: An Ideological Critique by Media Action Group (Ian Burn, Nigel Lendon, Terry Smith, Michael Dolk, Kieren Finnane, Mary Kinney, Ian Milliss, and Anne Sutherland); and its precursor We Are Not Happy Robots by On Our Own Time (Bruce Kaiper). It is now a long time since these works have been presented publicly, and it is likely that they were never screened in Europe.

1. We Are Not Happy Robots was made by Bruce Kaiper in 1976 and screened to various audiences of workers and activists in the Bay Area of California. In the previous year, Kaiper published his photo-essay "The Human Object, and its capitalist image” in Left Curve2, where he was then co-editor.

Both essay and slideshow share the same object of critique: modern manufacturing—its separation of manual and intellectual work, its privileging of the role of communication in production, and its gross augmentation of the managerial class. This is the story of the divorce between the head and the hand of the worker, as told by Marx, and again by Alfred Sohn-Rethel and Harry Braverman (of whom Kaiper owes much of his critique). A well dug out suspicion holds that Burn’s notion of the deskilling of art practice that occurred in the 1960’s and 70’s, first introduced to an art historical context in his essay Crisis & Aftermath (1981)3 , owes a debt to Braverman (via Kaiper). In “The Human Object”, Kaiper is first to apply a Marxist critique of the division of labour to a critique of the production of conceptual art. He concludes that the production of art in this manner (the privileging of intellectual labour over its manual counterpart, and the outsourcing of production) was reflective of modes of production in other economic spheres.

We Are Not Happy Robots addresses its audience more directly than its precursor, and the script reflects the values of the community of workers that Kaiper himself was a part of (it was designed to be presented over a lunch break). It is fundamentally concerned with how photography has aided in the degradation of work and image of the worker: in the contributions made to Scientific Management made by Frederick Taylor and Frank & Lillian Gilbreth in their use of time and motion studies; or the place of photography in modern advertising, where the worker is pictured as a miserable, aliquot part of the production process, marked for redundancy by technology. It recalls a broader remark on the aims of photography, and puts it to use: “The invention of photography. For whom? Against whom?”4

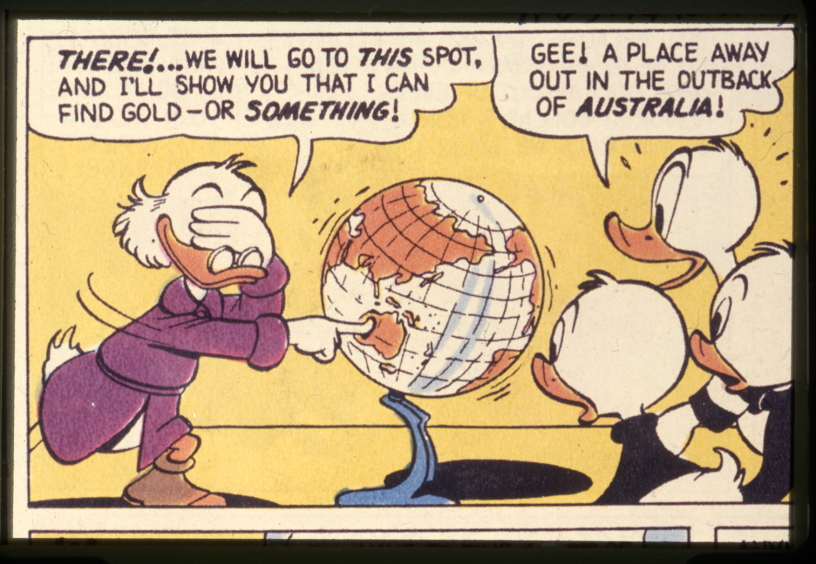

2. Media Action Group’s Walt Disney: An Ideological Critique (1979) revises the argument of Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart’s book of counter-imperialism "How to Read Donald Duck" for an Australian context. Dorfman & Mattelart’s book was written in Chile during the Socialist presidency of Allende, burned during the U.S backed dictatorship of Pinochet, and published in English by Seth Siegelaub. With many other books, it was partially responsible for an osmosis of the critique of ideology promoted by Louis Althusser into the general knowledge of the time. Its sentiment could be felt in Australia, where the Vietnam war had made American imperialism a palpable and common topic. At the time, Australian artists levelled criticism against visiting American artists and their advance of an “international” style—for example, Donald Judd was an unforgivable target, while Lucy Lippard, on her visit in 1975, endeavoured to be accommodating to criticism from the local community.5

Media Action Group refocused Dorfman and Mattelart's critique, and looked to Disney’s picturing of Australia (and the continent’s natural resources) as the site for the expropriation of wealth to the gains of power—Scrooge McDuck as mining magnate, in search of uranium during the Cold War… This slide-essay was made in a political atmosphere that included activism against the nuclear arms race and the residual socio-political effects that followed the end of the American occupation of Vietnam. It is due to these social facts that this document is indicative of a larger feeling among Australian artists of the time, and marks part of a transitional period for Burn (from artist, to critic and unionist).The sense of social responsibility held by the artists of Media Action Group is at the foreground of this work, where critique is measured out by plain language teaching. Indeed, its educational logic is inherent to its form. It was prepared for distribution as a teaching aid and integrated into art school curricula by Burn and his colleagues.

In March of 1976, Ian Burn moves to California from New York for approximately three months. After this he briefly visits Halifax, Nova Scotia where he is invited to teach at NSCAD, and makes a short trip back to New York City before terminally leaving Art & Language, conceptual art, and the United States in 1977 for work in the Australian union movement. What follows is a partial account of Burn’s contact with California and its influence on his later work with trade unions.6

Here he joins his peers Alan Sekula, Fred Lonidier, Martha Rosler and Phel Steinmetz at the University of California San Diego where he is invited as a guest professor. These artists shared certain political orientations, held aims for art to maintain a certain critical edge against society, and all took part in degrees of political activism. Notably, both Lonidier and Sekula were developing critical uses of photography as a means for social change, with considerable focus on working people and trade unions.

Two years later, in the winter of 1978, Alan Sekula’s Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary7 is published. In this essay Sekula discusses the work of his aforementioned peers in-depth, and notes the cultural work of Bruce Kaiper who was making critical use of the slideshow format in Oakland. With Kaiper’s We Are Not Happy Robots (1976) in mind, Sekula wrote that “A number of cultural workers in the Oakland area are using slide shows didactically and as catalysts for political participation [...] These shows are designed primarily for audiences of working people by people who are themselves workers." Through Left Curve, a journal then co-edited by Kaiper, Burn establishes correspondence. From Kaiper, Burn receives copies of We Are Not Happy Robots and takes these with him back to Australia. On his return, Burn joins Nigel Lendon and Terry Smith of Art & Language, as well as Michiel Dolk, Kieren Finnane, Mary Kinney, Ian Milliss, and Anne Sutherland to form the core of Media Action Group.8 Possibly led by Kaiper’s example, the group produces a number of slide-essays on socio-political topics, made especially for presentation to Australian trade unions, community activist groups, and students.

It is clear that these presentations were made under no pretension that they would be received as art. Rather, they were produced with a conscious application of the critical skills imported from their practices as artists and critics towards social and educational goals. For Burn, this was not an abandonment of art, but a renegotiation between its skills and the social relations in which it finds its object. The year earlier, in Artforum, Burn forecasted this move away from the "art world” and into political work:

"Whatever we are able to accomplish now, my point is that transforming our reality is no longer a question of just making more art—it is a matter of realising the enormous social vectoring of the problem [an art market unable to support the growing surplus of artists] and opportunistically taking advantage of what social tools we have.”9

Media Action Group would later became Union Media Services (UMS), a company that produced slideshows, journalism, design, and media for Australian trade unions. Amongst many projects, the work of UMS supported Art & Working Life, a program jointly administered by the Australia Council for the Arts and the Australian Council of Trade Unions, that focused on the cultural life of workers and the collaboration between artists and trade unions. The first of its kind.

Thanks to Avril Burn, Ann Stephen, David Homewood, Bruce & Ellen Kaiper, Nigel Lendon, Lucina Lane, Paris Lettau, Fred Lonidier, Deborah Mills, Terry Smith, Benjamin Thorel, Section 7 books, and Air de Paris.

This has been reconstructed from the remaining slides from the estate of Ian Burn, with the assistance of Nigel Lendon. ↩

Bruce Kaiper, “The Human Object, and its capitalist image”, Left Curve, No. 5, Fall-Winter 1975, p.40-60 ↩

In The 1960’s: Crisis & Aftermath, Burn identifies that Western art encountered a crisis in the 1960’s, where the question of skill was being redetermined by a whole new set of social and formal relations. Burn sees this as a rupture in the historical body of knowledge that is the production of art. Specifically, he writes of the division of labour inherent in the production of conceptual art: “What was witnessed with Conceptual Art was an absolute separation of mental or intellectual work from manual work, with a revaluing of the intellectual and a devaluing of the manual.”

This term has consequently been used by Benjamin Buchloh and John Roberts in differing applications. For their usage, see: John Roberts, “Art After Deskilling”, Historical Materialism, No. 18, 2010; Benjamin Buchloh, Gerhard Richter: Painting After the Subject of History, Ph.D. Dissertation, City University of New York, 1994. ↩

Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Pierre Gorin, Vent d’Est (1978) ↩

Karl Beveridge & Ian Burn, “Don Judd” in THE FOX #2, 1975; Ian Burn, Nigel Lendon, Terry Smith, “Why Do They Keep on Coming” in The Great Divide, 1977; Ann Stephen, On Looking at Looking: The art & politics of Ian Burn, The Miegunyah Press, 2006, p.170-171. ↩

This account is drawn from correspondence with Fred Lonidier and Bruce Kaiper, conversations with Ann Stephen, and draws on Stephen’s account in her biography of Burn: Ann Stephen, On Looking at Looking: The art & politics of Ian Burn, The Miegunyah Press, 2006 ↩

Sekula, Allan, ‘Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)’ (1978), in Photography Against the Grain, 1984 ↩

Ann Stephen, On Looking at Looking: The art & politics of Ian Burn, The Miegunyah Press, 2006, p.185 ↩

Burn, Ian, 'The art market: Affluence and degradation' (1975), Dialogue: Writings in Art History, 1991 ↩