Ian Burn et al. is a long research query focusing on the legacy of Ian Burn, and the work of his network of peers. A series of public events, publications and writing follows:

Ian Burn et al. is a long research query focusing on the legacy of Ian Burn, and the work of his network of peers. A series of public events, publications and writing follows:

Given Ian Burn’s commitment to leftist politics and his trenchant critiques of museums and the art market, it is likely that he would have objected to art-historical writing on his work on some level. As an artist who wrote about the art market and was troubled by how it may have permeated his work, Burn was clearly aware that art historical discourse is one of the principal ways that the market-value of artworks is increased under capitalism.1 In recognition of how the intellectual labour of the art historian is implicated in this process of valorisation, my intention in writing this essay is not to contribute to the cementing of Burn’s place as an individual artist within the Conceptual art movement (something that he actively tried to negate by working collaboratively), but instead to suggest how his lifelong concern with the issues of labour were already evident in his self-reflexive series of works, Systematically Altered Photographs (1968).

Burn was engaged with labour activist groups and unions throughout his life, and after he returned to Australia in 1977 this became his principal occupation. Burn worked with Union Media Services, an organisation that he co-founded to work on trade union publications. Throughout this period, he also promoted working class culture and art in the labour movement by writing social history, curating exhibitions, and by becoming a chief advisor and contributor to the Art and Working Life program run by the Australia Council for the Arts in partnership with the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU). In his 1981 essay, 'The Sixties: Crisis and Aftermath (Or Memoirs of an Ex-Conceptual Artist)', Burn contributed one of the earliest theories of the deskilling of art, suggesting that like the deskilling of labour in the workplace, artists too were subject to the separation of conception and execution in their work. Drawing on Harry Braverman’s Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, Burn compares artists to managers, as mere overseers of their own artistic production. The late 1960s, the time in which Burn’s work Systematically Altered Photographs was made, was a period characterised by vast economic restructuring in the United States, which shifted from an economy based largely on manufacturing, to one that experienced rapid growth in the service sector, particularly in finance, insurance, real-estate, health and education. Conceptual art has been read by a number of art historians as mirroring this shift. 2 Following these theorists, I will suggest that by adopting processes related to office-work in his work Systematically Altered Photographs Burn mimicked the growth of service-based and administrative labour which is characteristic of post-Fordism.

Burn made Systematically Altered Photographs in 1968, a year after he moved from London to New York with Mel Ramsden, his occasional collaborative partner and key interlocutor. The work was made as Conceptual art was beginning to take shape as a recognisable and self-conscious art movement, a year after Sol LeWitt published 'Paragraphs on Conceptual Art' in Artforum magazine. LeWitt identified a new kind of art emerging in the United States in which the idea or concept was the most important aspect of the work. 3 1968 was also a year of mass social movements, including protests over labour conditions in Europe and the USA, civil rights and the Vietnam War. This period in general was one of social upheaval in the capitalist countries of the West, which has been widely understood as a period of crisis within Fordism. Many Conceptual artists, including Burn, were involved with activist groups in New York that were part of these social movements, such as the Art Workers Coalition, founded in 1969 and Artist’s Meeting for Social Change.

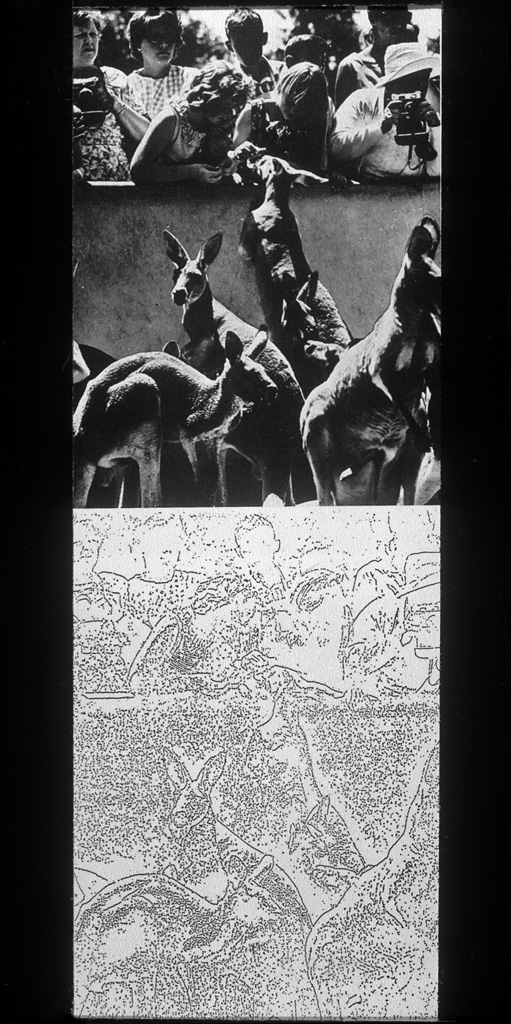

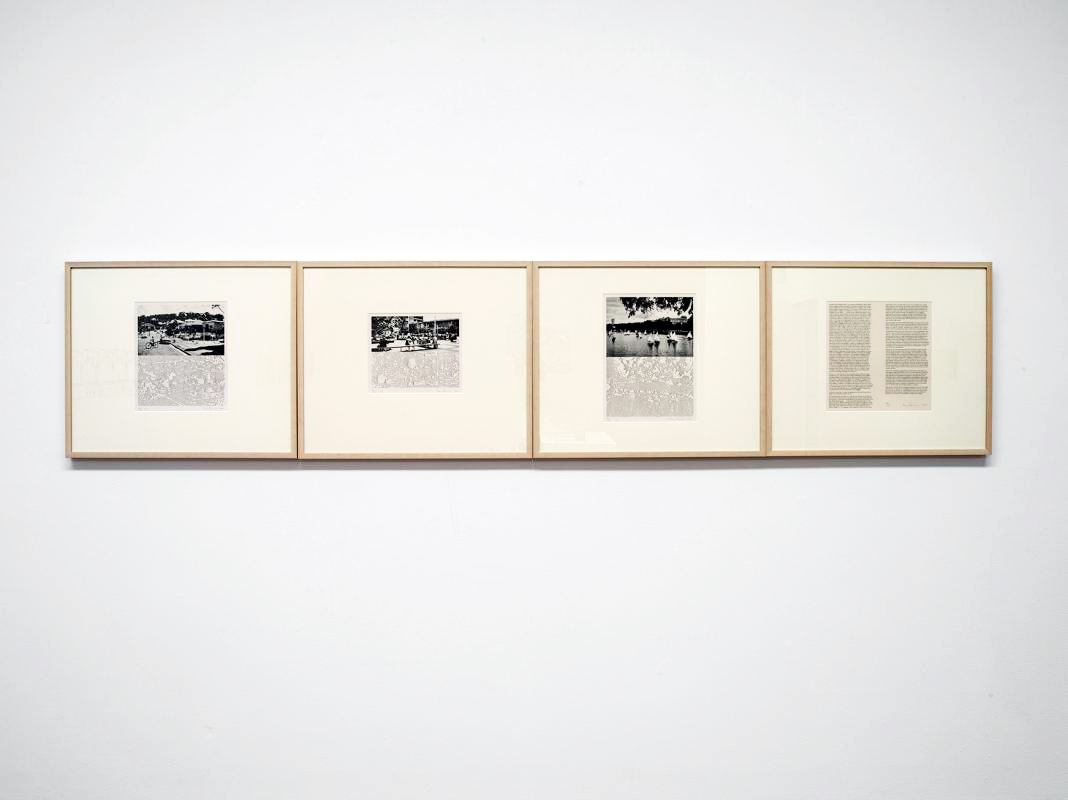

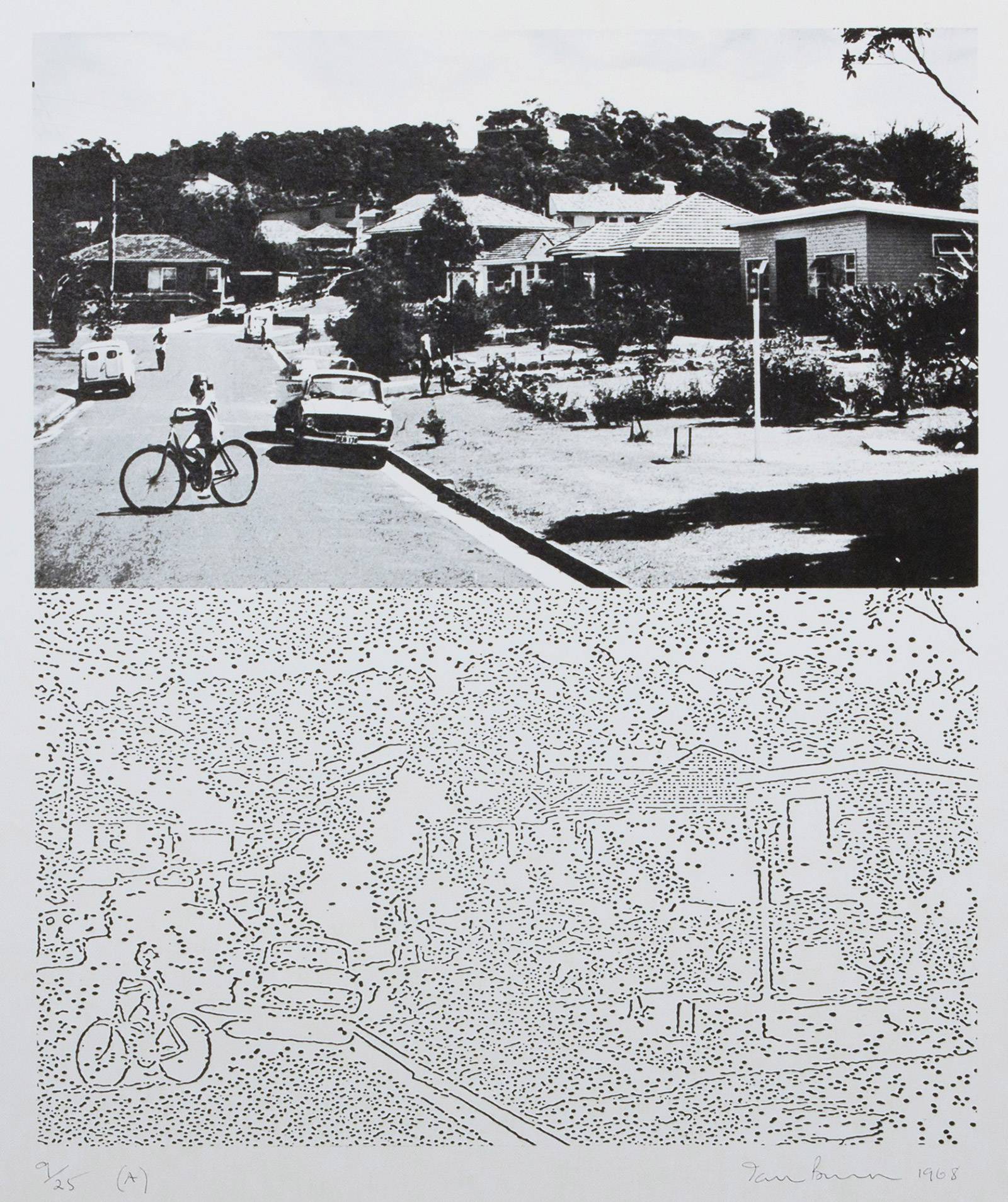

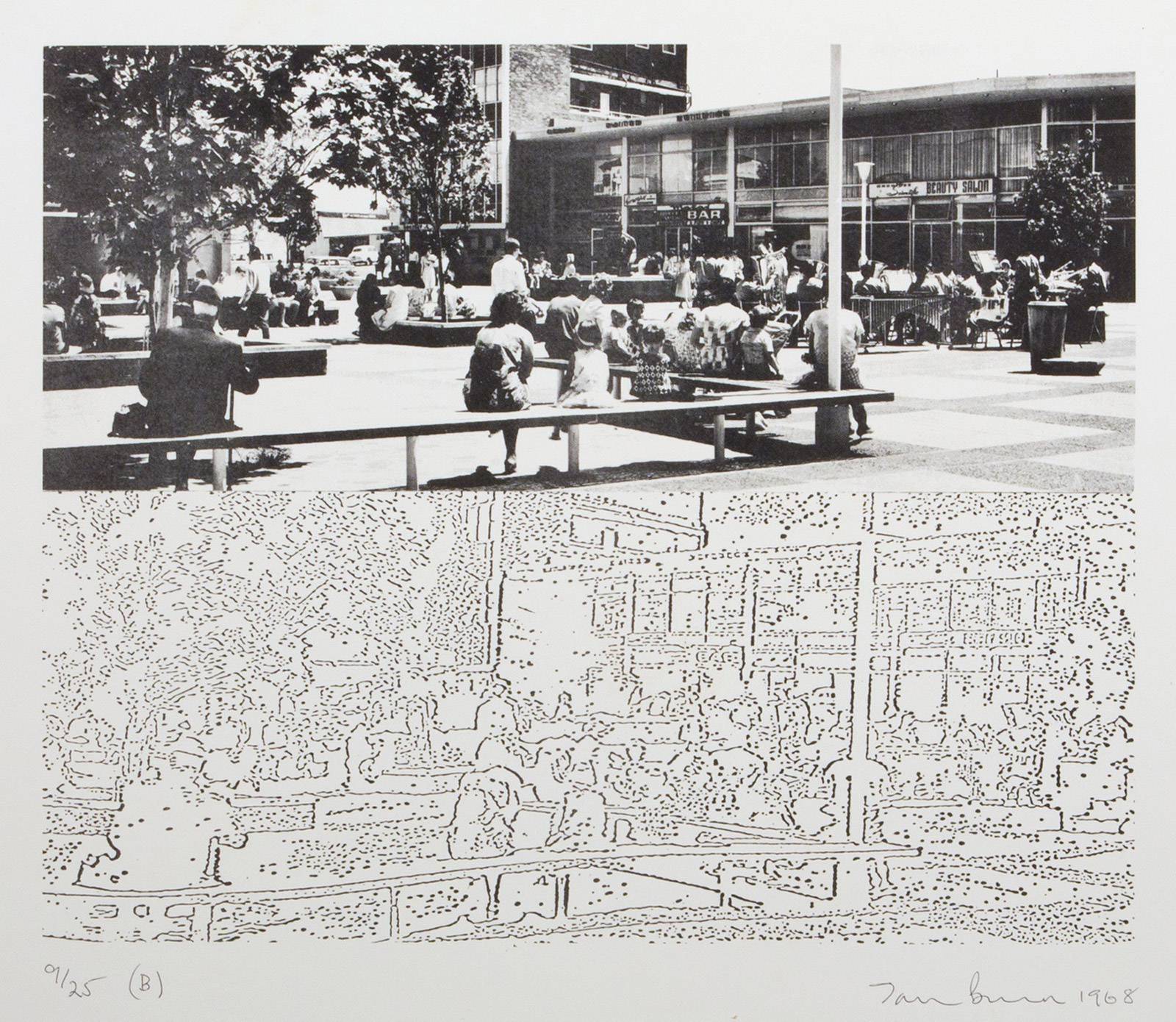

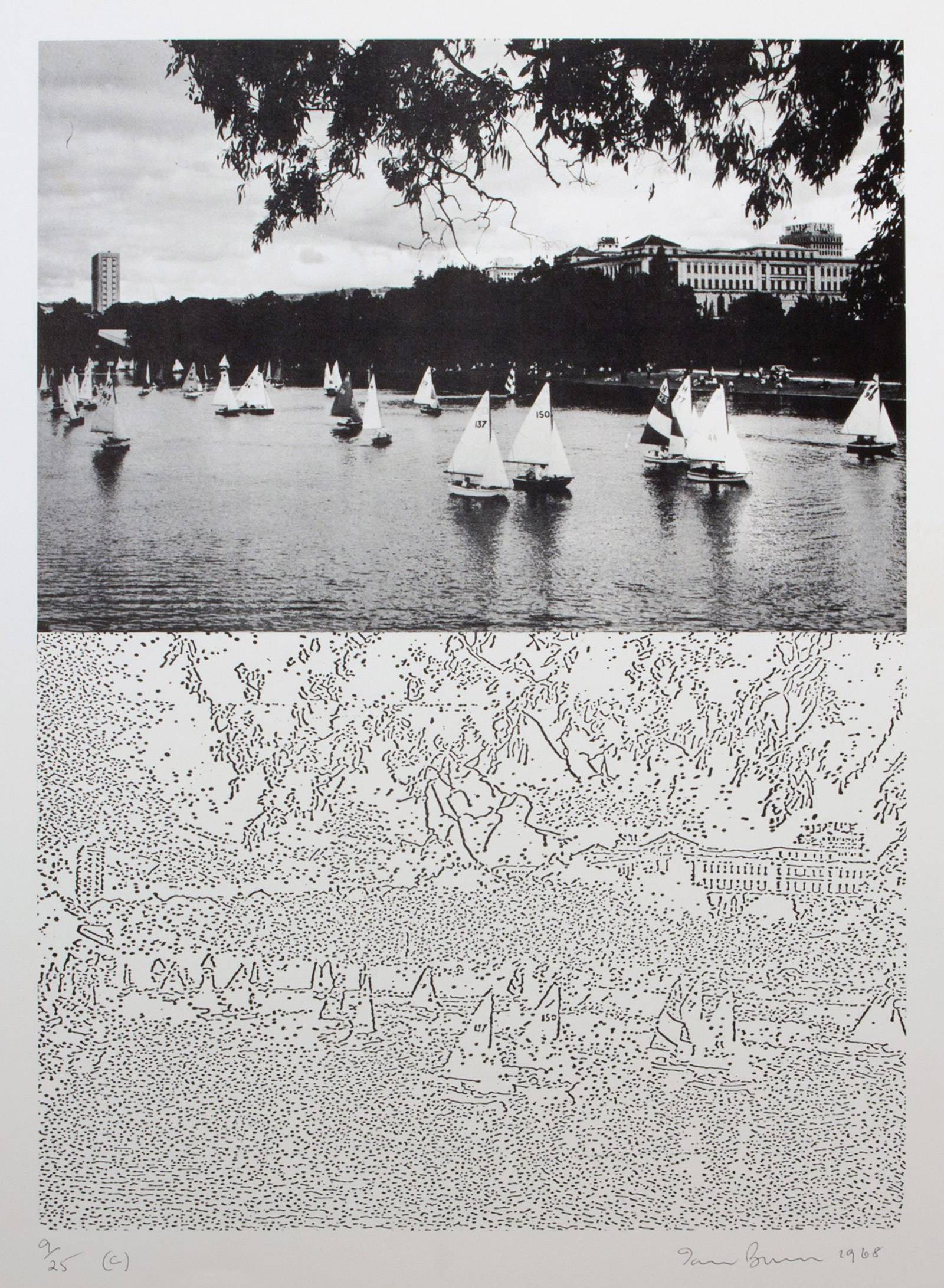

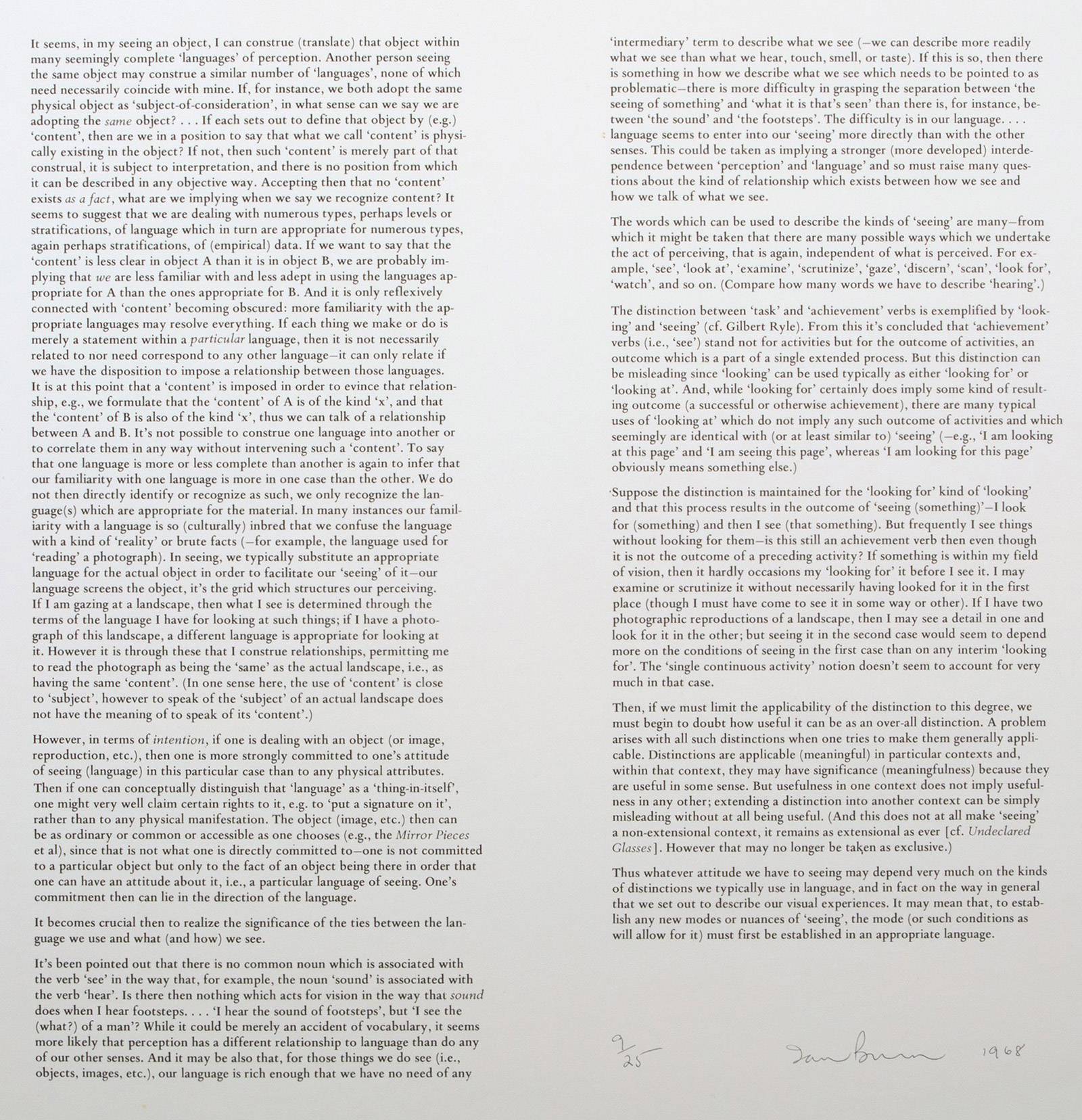

The particular work from this series that I am concentrating on is composed of four prints and bares the same title as the broader group of works made with the same process. It combines three black and white photographs taken from Australian Panorama—a promotional magazine distributed by the Australian government for international consumption—with an abbreviated version of Burn’s essay 'The Role of Language' (written in the same year). Australian Panorama was published by the Australian News and Information Bureau, which subsequently changed its name to the Australian Information Service—one of a number of government organisations created to promote a benign image of Australia structured by the government’s ideological aims. The contents of the magazine reflect this, focusing on an idealisation of Australian lifestyle, post-war migration, tourism and work. The 1967 issue of the magazine that Burn used as his source material was published at a time when Australia had escalated its involvement in the Vietnam War, promoting itself as an ally and partner to the United States. The three photographs appropriated by Burn for this work depict a generic suburban street, what appears to be a school yard and a tranquil scene of boats on a lake. Burn photocopied the images a number of times until they became schematic abstractions devoid of tonal differentiation. He then placed the disintegrated images, stripped of visual information and partially erased by the mechanical process of the photocopier directly underneath their corresponding original.

The juxtaposition of images and texts was a device frequently employed by Conceptual artists and, initially at least, it appeared to provide a means to challenge the demand placed on artists to produce visually pleasing and easily commodifiable art objects. By producing their own texts and including them as integral aspects of their works, Conceptual artists undermined the division of labour between artist and critic. They instigated the shift in artistic labour from manual craft skills to a new form of knowledge-work in which the idea took precedence. They engaged with how their works were produced, received and understood, loosening the critic’s privileged role in evaluating the work. In Systematically Altered Photographs the images and text are linked through Burn’s preoccupation with the issue of perception. By destroying the visual information in the photographs through the act of photocopying, Burn negates our ability to perceive them as images with an indexical relationship to the material world. Burn’s inclusion of part of his essay 'The Role of Language' in Systematically Altered Photographs can be read as a way to break with the Modernist idea that an art object can be understood on a purely visual level through unmediated contemplation, away from social concerns. Instead, Burn’s essay suggests that the visual and perceptual are structured by language, and this points to the idea that art objects are only comprehensible through the discourses and narratives that surround and legitimate them. Although Burn’s enquiry into the nature of the art object—self-reflexively structured around issues of perception—might seem consistent with the concerns of Modernist painting, in Systematically Altered Photographs he creates an obvious rift with the Greenbergian concept of artistic autonomy by bringing socio-political elements into his work. This is also made evident by the influence of Wittgenstein's philosophy on Burn’s essay 'The Role of Langauge', which dismissed any vantage point outside of language from which one might have access to intrinsic, universal meaning. Wittgenstein himself rejected the idea that meaning is equivalent to the direct apprehension of an object. For him, understanding was not a spontaneous process in which a visual impression of an object can be said to automatically impart meaning to it. What Wittgenstein’s philosophical account of meaning tried to demonstrate was the temporal nature of understanding, where a sign provides meaning once it has been subjected to a process of use through time. He claimed that the act of understanding was spontaneous, but the process behind it was not. Wittgenstein’s philosophy had important consequences for Conceptual art because it enabled artists to theorise encounters with art in ways divested of the idea of aesthetic immediacy. In contrast, Clement Greenberg’s Modernism was influenced by Gotthold Lessing’s Enlightenment account of the autonomous and separate characteristics of the arts, particularly the arguments he used in Laocoon, 1776, to differentiate between painting and literature. Lessing believed that literature was an essentially temporal art, whereas painting was essentially spatial. While reading literature occurs in time, he thought that the apprehension of painting was instantaneous. Greenberg’s Modernism sought to shore up this distinction, whereas Conceptual artists sought to negate it, and in Wittgenstein’s philosophy, they found an appropriate aid. As a result, the combination of image and text became an important strategy in Conceptual art’s devaluation of the visual in the work of art. 4

In 1974, Harry Braverman published Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, a book that examined the changing nature of work and the deskilling of the labour-force under monopoly capitalism in the United States. The aim of this book was to expand on the analysis of English manufacturing provided by Karl Marx in Capital by shifting the lens onto the Fordist manufacturing processes developed in the United States in the twentieth century. As Marx had suggested, the efficiency of the division of labour and the rise of machines in the manufacturing process lead to a loss of all-round craft skills and the production of a class of deskilled and interchangeable workers – the proletariat. Braverman extended this critique to include an analysis of scientific management, a method for controlling production devised in the late nineteenth century by Frederick Taylor through his ‘scientific’ experiments in the labour process; these were aimed at increasing the rate of production and making it more cost effective. Taylorism, in turn, influenced the assembly-line style of production pioneered by the Ford Motor Company, which became widespread in twentieth-century manufacturing and is often considered a historical extension of Taylor’s piecework. Taylor believed that more intense forms of control over the labour process should be exercised by management in order to increase productivity. Management could dictate each step in the production of a commodity by analysing and separating the roles performed by each worker to find the most efficient means to undertake a particular task. Consequently, this fragmented each role into smaller and smaller tasks and the menial repetition of piecework. Locating the origins of twentieth-century deskilling in Taylorism, Braverman argued that by insisting that management should control the knowledge associated with work Taylorism had led to the separation of conception and execution in production. The separation of conception and execution in production was a key point for Braverman. This meant that managers increasingly took control of the knowledge associated with production – a body of knowledge previously possessed by workers – and provided them with strict instructions to follow on specific and limited aspects of the production process. Workers were no longer able to apply a wide range of knowledge and skills but were subject to repetitive tasks. This, he argued, had a degrading effect upon workers. Braverman emphasised that this stripping of workers’ skills was part of a drive for increased capitalist accumulation.

While the deskilling of art in the 1960s has been seen by Burn and others as symptomatic of this broader trend in work outlined by Braverman, it also differed in a number of ways. Artists, while rejecting traditional craft skills, instead began to privilege intellectual skills, with the onus particularly in Conceptual art being on the idea. Additionally, it was the decision of artists to reject traditional skills, whereas this was not the case for either the factory or administrative workers described in Braverman’s account. Furthermore, the impetus for the deskilling of art was not the drive for heightened profit under rigorously supervised and more efficient forms of wage labour. Instead it was accompanied by a re-skilling that brought about an expansion of the possible forms that artistic labour could take. The reskilling of art as a form of intellectual work, not necessarily tied to objects created by the artist’s hand and in which ideas and research played an increasingly important role, was in part the result of changes in education. The generation of artists that emerged in New York in the 1960s were the first to study art within the university. The production of Minimalist art objects had already been subject to deskilling, with artists contracting out the manufacture of their work to companies devoted to industrial production. Due to this demand, new companies, such as Gemini G.E.L., Lippincott Inc. and Carlson & Co. emerged in the United States that dealt solely with the fabrication of works of art. 5 In the case of Systematically Altered Photographs, it is clear that the mostly automated process of photocopying and the selection of magazine photographs did not require traditional artistic skills. While Minimalist artists, such as Carl Andre and Robert Morris, imagined themselves as workers, mimicking the industrial, working-class forms of labour of the Fordist factory, Conceptual artists, such as Burn, used methods more in line with post-Fordist forms of work. Their work featured a proliferation of desks, Teletype machines, photocopies, type-written pages and the presentation of facts and statistical information, typically associated with office work. This is reflective of the vast changes in the capitalist economies of the West beginning in the 1960s. Manufacturing moved towards a globalised 'just-in-time' model of production, as capitalists sought out cheaper labour markets by relocating production to countries in Asia, South America and Eastern Europe. This resulted in a huge pool of increasingly casualised clerical workers in the West.

Bibliography

Braverman, Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. London and New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia. Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam Era. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2010.

Burn, Ian, Dialogue: Writing in Art History, Sydney: Allen and Unwin Pty Ltd, 1991.

Child, Danielle. “Dematerialization, Contracted Labour and Art Fabrication: The Deskilling of the Artist in the Age of Late Capitalism.” Sculpture Journal 24.3 (2015) 275

Harvey, David. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change, Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1989.

Osborne, Peter, Conceptual Art, London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2002.

Roberts, John. “Art and the Problem of Immaterial Labour: Reflections on Its Recent History,” in Economy: Art, Production and the Subject in the 21st Century, edited by Angela Dimitrakaki and Kirsten Lloyd, 49-56. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015.

Roberts, John. The Intangibilities of Form: Skill and Deskilling in Art After the Readymade. London and New York: Verso, 2007.

Stephen, Ann. On Looking At Looking: The Art and Politics of Ian Burn. Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press, 2006.

Roberts, John. “Photography, Iconophobia and the Ruins of Conceptual Art,” in The Impossible Document: Photography and Conceptual Art in Britain 1966 – 1976, edited by John Roberts, 7 – 45. London: Cameraworks, 1997.

Ian Burn, “The Art Market: Affluence and Degradation,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 1999), 321. ↩

See Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009); Helen Molesworth, ed. Work Ethic (Baltimore: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003); Buchloh, Benjamin. “Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions,” October 55 (Winter 1990): 105-143. ↩

Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 1999), 12. ↩

John Roberts, “Photography, Iconophobia and the Ruins of Conceptual Art,” in The Impossible Document: Photography and Conceptual Art in Britain 1966 – 1976, ed. John Roberts (London: Camerawork, 1997), 20-21. ↩

Danielle Child, “Dematerialization, Contracted Labour and Art Fabrication: The Deskilling of the Artist in the Age of Late Capitalism,” The Sculpture Journal 24, issue 3 (2015): 378. ↩

Ian Burn, “The Sixties: Crisis and Aftermath (or the Memoirs of an Ex-Conceptual Artist),” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 1999), 402. ↩

Alexander Alberro, “Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966 – 1977” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 1999), xxix. ↩

Ian Burn, “The Sixties: Crisis and Aftermath (or the Memoirs of an Ex-Conceptual Artist)” 394. ↩

Mel Ramsden, “On Practice,” The Fox, issue 1, (1975): 83. ↩